The betting problem.

Managing inventory usually feels like a gambling addiction. You place a wager on how much product you need, and the market either rewards you or punishes you. Order too much, and your cash gets trapped in a warehouse, gathering dust. Order too little, and you face the nightmare scenario: stockouts and lost revenue.

Most inventory managers treat this as a "gut feeling" exercise. But that’s not you.

You are looking for the point where the math stops you from bleeding money. This is where Economic Order Quantity (EOQ) steps in.

EOQ is the calculation that identifies the ideal order size to minimize costs. It removes the emotion from purchasing and replaces it with efficiency. We are going to break down the variables, walk through the formula using real numbers, and then look at how modern AI is rewriting the rules of this decades-old concept.

The Core Concept: Balancing Two Opposing Costs

The tug-of-war.

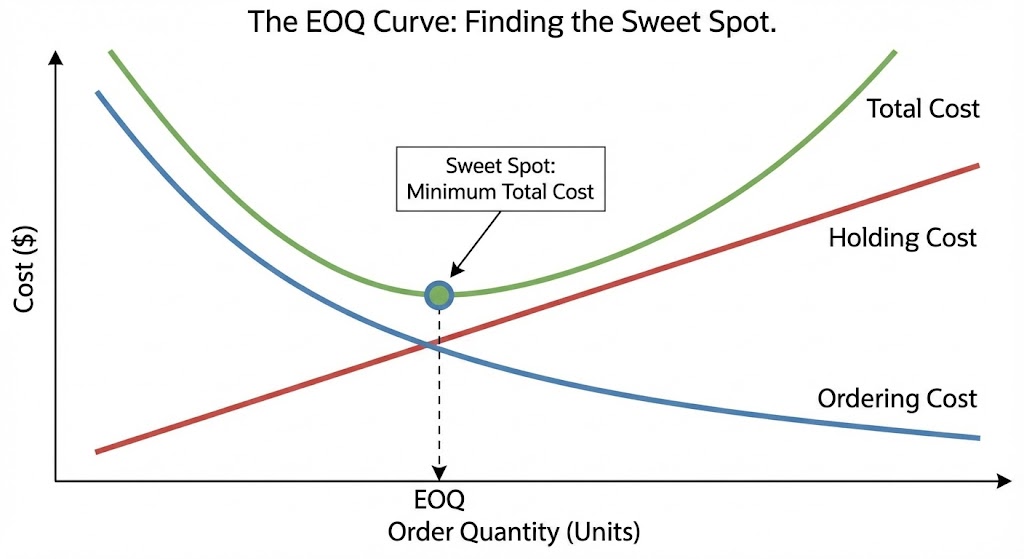

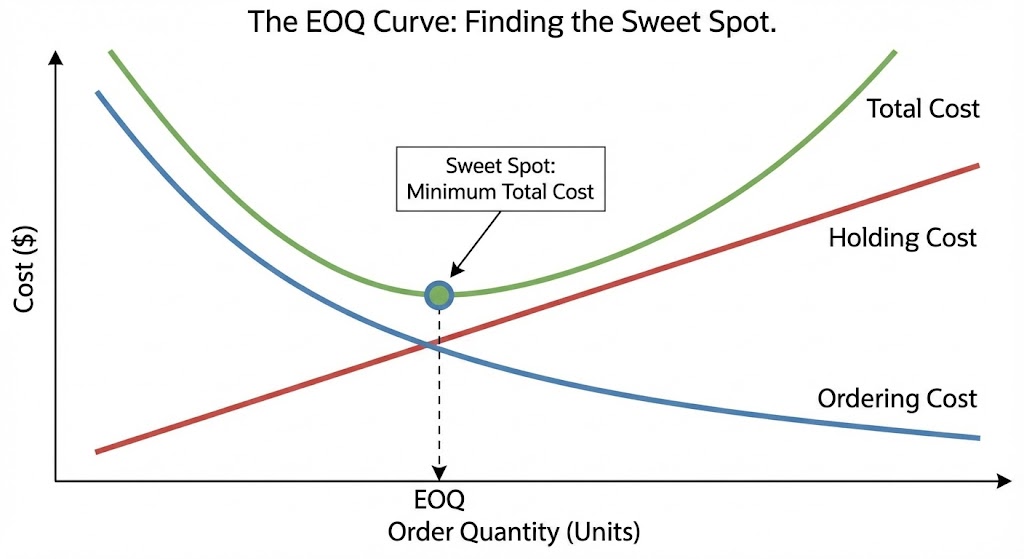

Inventory management fights a battle between two financial enemies that pull your business in opposite directions: Ordering Costs and Holding Costs.

On one side, you have Ordering Costs. These are the expenses you pay every time you contact a supplier. The logic is simple: if you order massive batches, your ordering costs plummet because you pay for shipping and setup less often.

On the other side, you have Holding Costs. These are the silent budget-killers—the costs of storing and insuring stock. The more you order at once, the heavier this burden becomes. Your warehouse fills up. Your insurance premiums rise. Your cash is tied up in physical goods rather than growth-driving initiatives.

Finding the bottom of the curve.

If you graph these two costs, they form an "X." Somewhere in the middle, there is a single point where the combined cost of ordering and holding is at its absolute mathematical minimum.

That point is the EOQ. It creates a balance—ensuring you aren't wasting cash on frequent, tiny orders, nor drowning in excess stock.

The Three Pillars (Variables) of EOQ

To solve the puzzle, you need three specific pieces of data.

D = Annual Demand (in units)

This is the total number of units you expect to sell over the coming year.

Don't just look at last month and multiply by twelve. You need to look at historical data to get a number that reflects reality. If you operate in a volatile market, this number can be tricky (we’ll discuss how AI fixes this later), but for the standard formula, you need a solid annual estimate.

S = Order Cost (per order)

This variable represents the flat fee associated with processing a purchase order.

Crucially, this is not the purchase price of the widget itself. This is the cost of the action of ordering. It includes shipping fees, handling charges, and the hourly wage of the procurement manager creating the PO. Whether you order 1 unit or 1,000 units, this setup cost remains largely the same—which is why high order costs encourage bulk buying.

H = Holding Cost (per unit, per year)

This is the cost to store a single unit for one full year.

Businesses often miscalculate this variable. It includes warehousing rent, utilities, security, and insurance. But the biggest component is opportunity cost (the money sitting on a shelf that isn't growing). A good rule of thumb? Holding cost is usually 20% to 30% of the total inventory value.

The Formula and Calculation

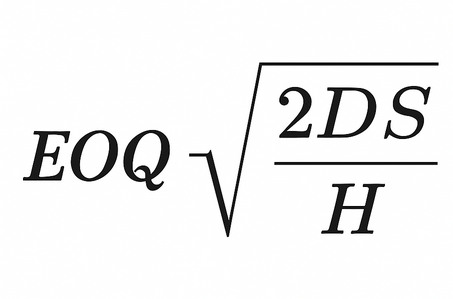

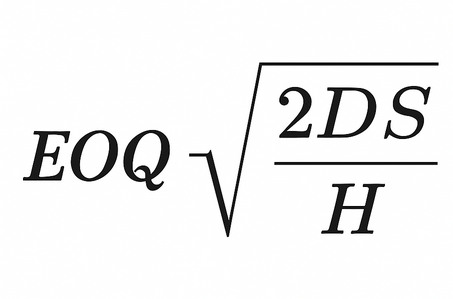

Now that we have our variables, we can plug them into the framework. The formula is a simple way to slice through the noise.

The Formula

It reads as: The square root of (2 times Annual Demand times Order Cost) divided by Holding Cost.

Step-by-Step Example

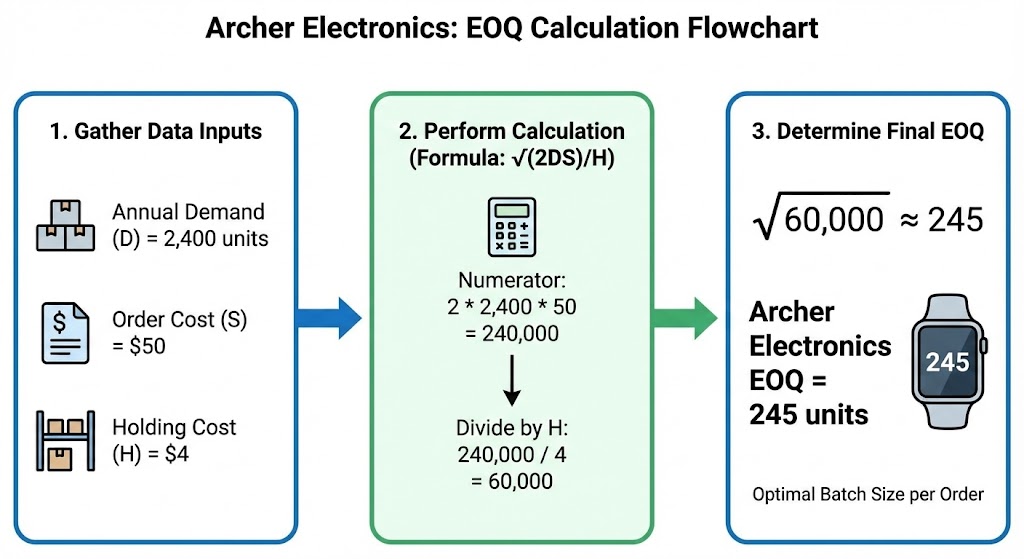

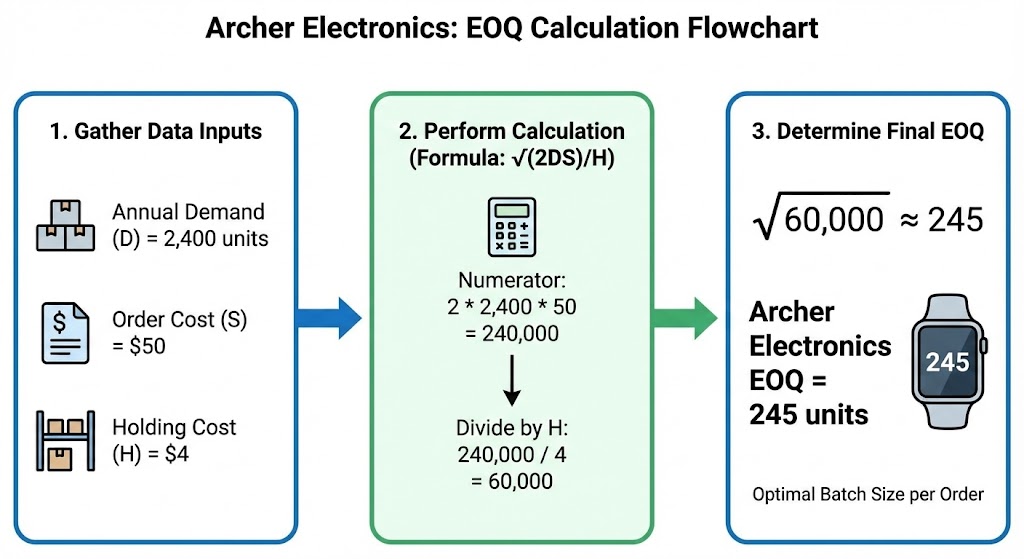

Let’s apply this to a real-world scenario.

The Scenario: "

Archer Electronics" sells 2,400 smartwatches a year. They want to know exactly how many watches to buy in a single batch to keep costs low.

The Variables:

- $D$ (Annual Demand) = 2,400 units.

- $S$ (Order Cost) = $50. (This covers the admin time and shipping setup for each order).

- $H$ (Holding Cost) = $4. (It costs $4 to keep one watch on the shelf for a year).

The Math:

- Multiply the numerator:

$2 \times 2,400 \times 50 = 240,000$

- Divide by the denominator (Holding Cost):

$240,000 / 4 = 60,000$

- Take the square root:

$\sqrt{60,000} \approx 245$

The Result:

Archer Electronics should order 245 units at a time.

If they order more than 245, their holding costs will eat their profits. If they order fewer, their ordering costs will spike. 245 is the mathematical "sweet spot."

Frequency check.

Once you have the EOQ, you can determine your rhythm. If Archer needs 2,400 units a year and orders 245 at a time, they will place roughly 10 orders per year ($2,400 / 245 = 9.8$). This turns a vague strategy into a concrete schedule.

Critical Limitations: When EOQ Fails

The static-world fallacy.

The standard EOQ formula assumes you live in a reality where customers buy products evenly and suppliers deliver instantly. Real supply chains are messy. They are full of friction and human error.

Where the math breaks.

- Constant Demand: The formula ignores seasonality. If you sell swimsuits, your "annual demand" is useless in December. Using a flat EOQ here leaves you overstocked in winter and stocked out in summer.

- Instant Replenishment: It assumes stock arrives the moment you order it. It ignores lead times. If you hit your reorder point and the boat gets stuck, the math won't save you.

- Static Costs: It assumes purchase price doesn't change. If a supplier raises prices next month, your previous EOQ calculation is instantly obsolete.

Using EOQ blindly in a volatile market causes trouble—but understanding these limitations allows you to use the number as a baseline.

Modern Alternatives and Adjustments

Supply chain management has evolved from pen-and-paper math to predictive intelligence. Here is how modern businesses upgrade the old formula.

EOQ with Quantity Discounts

Buying in bulk.

Sometimes, the math says "order 245 units," but the supplier says, "If you order 500, I'll drop the price by 10%."

In this case, the lower purchase price might outweigh the higher holding cost. You need to run a Quantity Discount Model calculation to see if the savings justify the heavier inventory load. High-volume discounts often subsidize the cost of extra warehousing.

Just-in-Time (JIT)

The zero-inventory approach.

This methodology rejects the idea of "holding" inventory entirely. Instead of optimizing batch sizes, JIT aims to reduce Setup Costs ($S$) and Holding Costs ($H$) to near zero.

The goal here is flow—materials arrive exactly when production needs them. In a JIT environment, the EOQ formula is irrelevant because the goal is not to balance costs, but to eliminate storage.

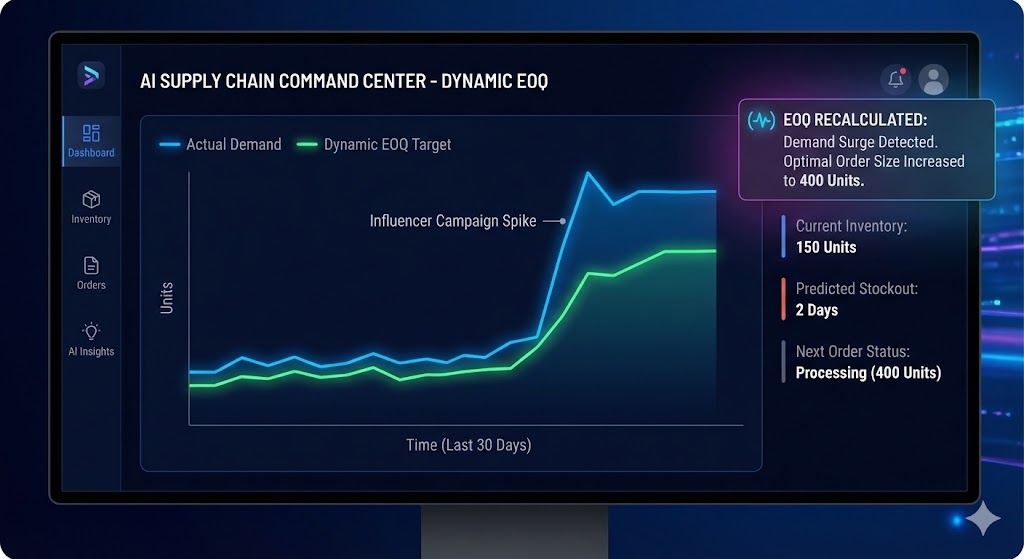

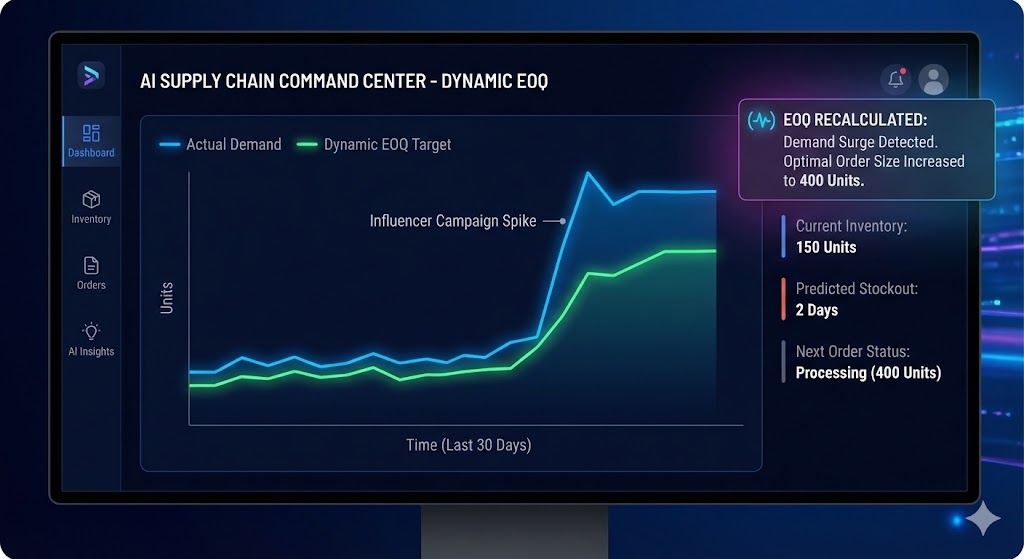

AI and Dynamic EOQ

The living number.

Modern ERP systems don't just use a static "D" for demand. They use machine learning to create a Dynamic EOQ.

These systems analyze real-time trends, weather patterns, and marketing campaigns to adjust the "Demand" variable week-to-week.

Instead of a single EOQ number for the year, you get a number that breathes with the market. If an influencer mentions your product and demand spikes, the system recalculates the optimal order size instantly—ensuring you capture the revenue without blowing up your storage costs.

Conclusion

Baseline, not law.

EOQ gives you a starting point for efficiency. It cannot survive the friction of the real world on its own.

Start with the formula to understand your financial baseline. But as you scale, you will need to layer in modern software to adjust for lead times and seasonality. Your inventory strategy—for you—is a living system. Keep measuring. Keep optimizing.